Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Injury

The Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint is a common site of injury, particularly, for athletes involved in contact and collision sports such as Australian football and rugby (league and union), and throwing sports such as shotput.

Anatomy

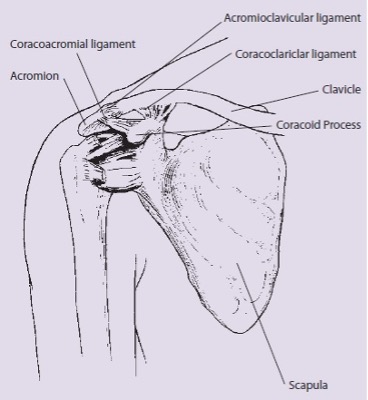

The AC Joint makes up part of the shoulder structure. It is the point at which the lateral end of the clavicle (collar bone) meets with the part of the scapula (shoulder blade) called the Acromion Process. It can be identified by sight and touch as the pointy protrusion near the top, outer edge of the shoulder.

The joint is surrounded by a joint capsule and is provided additional support by the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments (the coracoclavicular ligament is made up of the trapezoid and conoid ligaments). The acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments are usually damaged in the most common injuries to the AC Joint.

Risk

An AC Joint injury often occurs as a result of a direct blow to the tip of the shoulder from, for example, an awkward fall, or impact with another player. This forces the Acromion Process downward, beneath the clavicle.

Alternately, an AC Joint injury may result from an upward force to the long axis of the humerus (upper arm bone) such as a fall which directly impacts on the wrist of a straightened arm. Most typically, the shoulder is in an adducted (close to the body) and flexed (bent) position.

Prevention

- Wearing protective strapping to support a previously injured AC Joint, particularly in contact sports or sports where full elevation of the arm is not so important. Protective padding is also used in sports such as rugby.

- Warming up, stretching and cooling down.

- Participating in fitness programs to develop strength, balance, coordination and flexibility.

- Undertaking training prior to competition to ensure readiness to play.

- Gradually increasing the intensity and duration of training.

- Allowing adequate recovery time between workouts or training sessions.

- Wearing the right protective equipment, including footwear.

- Drinking water before, during and after play.

- Checking the sporting environment for hazards prior to training and match play.

- Avoiding activities that cause pain. If pain does occur, discontinuing the activity immediately and commencing RICER.

Signs and Symptoms

- Pain at the end of the collar bone.

- Pain may feel widespread throughout the shoulder until the initial pain resolves; following this, it is more likely to be a very specific site of pain over the joint itself.

- Swelling often occurs.

- Depending on the extent of the injury, a step-deformity may be visible. This is an obvious lump where the joint has been disrupted and is visible on more severe injuries.

- Pain on moving the shoulder, especially when trying to raise the arms above shoulder height.

There are various grading scales for AC Joint injuries. Most grading scales range from 1–3 as shown in the table below:

| Grade | Description |

| 1 (mild) | An athlete with a grade 1 injury of the AC joint will experience tenderness and discomfort, palpation and movement of the joint. Grade 1 sprains involve only partial damage to the joint capsule and the AC ligament. Return to play – up to 3 weeks. |

| 2 (moderate) | A grade 2 injury will involve complete rupture of the acromioclavicular ligament and partial tear of the coracoclavicular ligament. This tearing allows the clavicle to move upward, and as a result, the bump on the shoulder is more pronounced. Pain is more severe and movement of the shoulder is restricted. Return to play – minimum 4 to 6 weeks. |

| 3 (severe) | A grade 3 injury involves the complete rupture of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments. The bump visible in a grade 2 tear is even more pronounced in a grade 3 injury due to complete dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint. Return to play – dependent on management (e.g. surgery). |

Immediate Management

The immediate treatment of any soft tissue injury consists of the RICER protocol – rest, ice, compression, elevation and referral. RICE protocol should be followed for 48–72 hours. The aim is to reduce the bleeding and damage within the joint. The shoulder should be rested in an elevated position with an ice pack applied for 20 minutes every two hours (never apply ice directly to the skin). The arm should also be immobilised in a sling. This may be for as little as two days in a mild injury, or up to six weeks in a more severe case.

The No HARM protocol should also be applied – no heat, no alcohol, no running or activity, and no massage. This will ensure decreased swelling and bleeding in the injured area.

A sports medicine professional should be seen as soon as possible to determine the extent of the injury and to provide advice on treatment required. A sports medicine professional may perform a physical examination and take x-rays of the shoulder.

Rehabilitation and Return to Play

Most AC Joint injuries are treated conservatively using various combinations of strengthening exercises, following the immobilisation phase, once pain permits. Surgery is usually reserved for cases where there is a complete dislocation of the AC Joint (Grade 3), or in cases where a less severe injury fails to respond adequately to conservative treatment.

Acknowledgements

Sports Medicine Australia wishes to thank the sports medicine practitioners and SMA state branches who provided expert feedback in the development of this fact sheet.

Images are courtesy of www.istockphoto.com

Always Consult a Trained Professional

The information above is general in nature and is only intended to provide a summary of the subject matter covered. It is not a substitute for medical advice and you should always consult a trained professional practising in the area of sports medicine in relation to any injury. You use or rely on the information above at your own risk and no party involved in the production of this resource accepts any responsibility for the information contained within it or your use of that information.